Jiddu Krishnamurti’s Book Summary What is Mind

- by greatsurajitgenius@gmail.com

- in Uncategorized

- on August 24, 2025

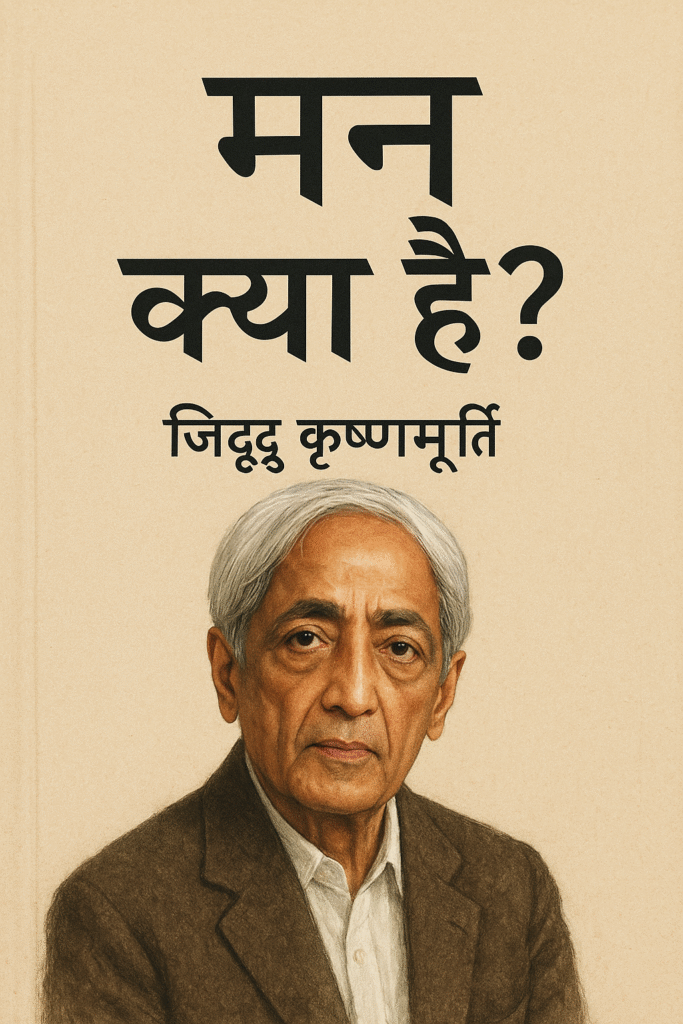

Jiddu Krishnamurti — Man Kya Hai? (What is Man?)

A clean, professional summary in simple English: introduction to Krishnamurti, introduction to the book, and a three‑part summary.

Introduction to Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) was a global teacher who questioned all forms of religious, political, and psychological authority. Discovered as a boy by leaders of the Theosophical Society and once expected to become a world teacher within their organization, he famously dissolved the Order of the Star in 1929, declaring that “truth is a pathless land.” From then on he spoke independently across continents for over five decades. His talks and dialogues invite listeners to look directly at their own minds, to understand fear, desire, conditioning, and the sense of self without following any guru, scripture, or method. Krishnamurti’s core emphasis is on choiceless awareness—observing what is happening in ourselves and in relationship without judgment or escape—so that the mind becomes clear, intelligent, and compassionate.

Introduction to the Book

Man Kya Hai? (What is Man?) gathers Krishnamurti’s insights on the nature of human existence. The book does not present a system to believe in; it acts as a mirror, inviting us to observe ourselves carefully. It asks what man really is when we set aside second‑hand answers from science, religion, and ideology. Through simple yet penetrating inquiry, Krishnamurti shows that to understand man is to understand oneself in everyday life—our thoughts, fears, desires, relationships, and the idea of “me.”

Summary — Part 1

Man Kya Hai? begins by asking a basic question: what is man? We usually expect ready answers from religion, science, or psychology, but Krishnamurti points out that such answers become beliefs and do not bring real understanding. He proposes a different approach: begin with direct observation. Look at your own life, the movement of thought and feeling, the way you react, the way you seek security. This looking is the key to understanding what man is, because each of us holds the story of humanity within.

Krishnamurti explains that we experience ourselves as a separate, permanent “I,” but this sense of self is made of thoughts, images, memories, and conditioning. When anger arises, the mind says “I am angry,” as if the “I” is separate from anger. If we watch closely, we see the “I” thought appears with the feeling; the thinker and the thought are not two different things. The same is true for fear, jealousy, or desire. The observer is the observed. Seeing this breaks a central illusion and ends a lot of inner conflict created by the idea of a controller struggling against what he himself is.

From here the book looks at conditioning. Family, culture, religion, education, and experience shape the brain to respond in fixed patterns. We carry labels—Hindu or Muslim, believer or non‑believer, rich or poor, successful or failure—and these labels filter our perception. Because of conditioning, we react mechanically to praise and blame, success and failure. We feel proud when approved and hurt when criticized. Krishnamurti compares this mechanical living to a computer running a program. If you were born in a different country or faith, your beliefs would likely be different; this shows belief is conditioning, not truth.

How do we understand conditioning? Not by analysis or suppression, but by simple, sustained observation in daily life. When irritation, envy, or fear appears, watch it without naming, judging, or escaping. The very movement of escape—through entertainment, ideals, or spiritual practices—keeps the problem alive. If the mind stays with what is actually happening, without the interference of an observer separate from it, the pattern begins to reveal itself and to end.

The first part also explores psychological time. Physical time is needed for learning a language or growing a plant. But the mind invents another time—made of memory and projection. We carry yesterday’s hurts and tomorrow’s hopes, and this movement of past‑future keeps us in conflict. You remember an insult and feel pain again today; you imagine failure and feel anxiety now. The “me” depends on this psychological continuity. When thought quiets and the mind meets the present without the weight of yesterday and the fear of tomorrow, there is freshness and freedom. This is not a theory but something to discover by watching the mind moment to moment.

Summary — Part 2

In the middle of the book, Krishnamurti looks closely at everyday problems—dependence, relationship, desire, fear, and suffering. He says man depends on people, possessions, position, and belief to feel safe. Dependence breeds fear of loss and jealousy. In relationship we rarely meet each other directly; we meet through images built from memory: what you did yesterday, what I expect tomorrow. These images stand between us and create conflict. Where images operate, love withers, because love is alive only in the present, not in the past.

He explains the birth of desire: there is seeing, then sensation, then thought creates an image of having or avoiding, and from that image comes the “I want.” Desire itself is not a sin, but when the mind is dominated by desire, it becomes restless—always chasing, rarely content. Watching desire as it arises, without condemning or indulging, reveals its structure and loosens its grip.

Fear, Krishnamurti says, is always tied to thought and time. Thought remembers pain or imagines danger and produces fear now. Without the activity of thought, psychological fear cannot exist. Immediate physical danger calls for quick, intelligent action; psychological fear is the shadow of memory and projection. Can we look at fear without escape? If we stay with fear, without naming or running, we see how it is woven from thought. In that direct seeing, fear begins to end.

Suffering is universal—loss, loneliness, frustration, and grief. Escapes—belief, distraction, entertainment—do not end suffering. Krishnamurti asks if we can hold suffering gently, without resistance. When we do, a deep understanding awakens: our pain is not just personal; it is the shared story of mankind. From this insight there flowers a compassion that is not sentimental. It is born from perceiving our common humanity.

All this points back to the central issue: the self. The “me” is a movement of memory, desire, and fear seeking continuity and becoming. This movement divides: me and you, us and them, what I am and what I should be. As long as this center operates, there will be conflict inwardly and outwardly. The question is not how to discipline the self but whether this movement can end. When it is seen that the observer is the observed—that the controller is the controlled—the division collapses. In the ending of that division there is a natural, effortless quietness. Krishnamurti calls this quietness meditation—not a practice, method, or repetition, but the silence that comes when awareness is choiceless and complete.

Summary — Part 3

In the final movement, the book turns to freedom, love, death, and transformation. Freedom is not doing what we like or choosing between options; choice indicates confusion. When there is clear seeing, action is direct. Real freedom is the absence of the self, because the self—made of fear, desire, and memory—is the root of bondage. Without the activity of the self, the mind is simple, clear, and alive.

Love, in Krishnamurti’s view, is not attachment or dependence. Where there is fear of loss, jealousy, or possession, love cannot be. Love is not a thing to cultivate by will or method; it appears naturally when the mind is free of fear and the movement of becoming. In such love there is compassion and a sense of unity with all life, without belonging to any ideology or group.

Death is usually something we push to the future and fear. We fear the ending of the known: relationships, property, memories, and the image of “me.” Krishnamurti asks whether we can “die” each day to the past—drop yesterday’s hurts and pleasures—so the mind is fresh. Meeting life with a mind that is ending the past from moment to moment removes the sting of death. Then death is not a threat but part of the beauty of living.

Transformation, the book insists, is not gradual. Time does not free the mind; time only prolongs conditioning. Change happens in the instant of seeing the true. If it is seen deeply that comparison breeds envy, comparison ends. If it is seen that the thinker and thought are one, the struggle between controller and controlled drops away. Such perception is not intellectual; it is like seeing a cliff’s edge and stepping back at once. No authority, method, or guru can deliver this; truth is a pathless land and must be discovered directly, now.

Krishnamurti returns finally to the fact that each one of us is the story of all humanity. To understand oneself is to understand mankind. When even one mind is free of fear and conditioning, it becomes a light to others—not through preaching or example to copy, but simply by living with clarity and compassion. In the natural stillness that comes when the movement of the self ends, there is a different kind of intelligence—impersonal, sensitive, and caring. In that intelligence there is harmony with people, nature, and action.

Made for study and reflection. Print‑friendly. Simple English. — © Your Notes